|

Email a link to this page to someone who might be interested. Internet Explorer is the only browser that shows this page the way it was designed. Your computer's settings may alter the display. You can go home again (thanks to our citizen soldiers of many wars). This page was published January, 2006. A shorter tribute Web page for Darold Henson appears on the Web site of the World War II Illinois Veterans Memorial and is titled Darold Henson Served in Three Campaigns of the European Theater of Operations (click underlined text to access that Web page tribute.)

April 24, 2004: Awarded "Best Web Site of the Year" by the Illinois State Historical

Society "superior

achievement: serves as a model for the profession and reaches a greater

public" |

|

|

|

Marquee Lights of the Lincoln Theatre, est. 1923, Lincoln, Illinois |

|

A Tribute to Lincolnite Edward Darold Henson (1918--2008), |

|

World War II U.S. Army Veteran of |

|

the Battles

for Normandy and the Hedgerows,

by Darold Leigh Henson,

Ph.D.

"I had help." --Darold Henson, 12-05.

(Link to

Conclusion.) |

|

|

Darold Henson (1944) |

Darold Henson in 2nd Inf.

Div.

Cap (2002) |

|

Military Organization and Leadership of the United States First Army Darold Henson was a member of the 2nd Infantry Division, 38th Regiment, Company M, of V Corps. The 2nd Infantry Division was/is known as the Indian Heads, and their motto was/is "Second to None." V Corps and VIII Corps, led by Major General Troy H. Middleton, composed the First Army, led by. Lt. General Courtney Hodges. Omar Bradley was commander of all U.S. forces in Europe. Dwight Eisenhower was the Supreme Allied Commander over American, British, Canadian, and other Allies in the European Theater.

Lt. General (later General) Courtney H. Hodges (1888-1966) (photo from John S. D. Eisenhower, The Bitter Woods, unnumbered page)

V Corps of the First Army was led by Major General (later General) Leonard

T. Gerow, and the 2nd Infantry Division was led by Major

General Walter M. Robertson (Parker, p. 304). The commanding officer of the

38th Regiment was Colonel Francis H. Boos (The Bitter Woods, p. 223). |

|

|

Major General (later General) Leonard T. Gerow (photo from The Bitter Woods, unnumbered page) |

Maj. General Walter M. Robertson (photo from A Time for Trumpets, p. 250) |

|

Since Darold's WW II experience was directly affected by Robertson's leadership, I summarize his background: Walter Melville Robertson, a member of an old Virginia family, graduated from West Point in 1912. He was not overseas during WW I. Between wars, he commanded infantry regiments in various remote posts in the West and Southwest. He was also an instructor at the Army War College. In 1940 he joined the 2nd Infantry Division at Fort Sam Houston near San Antonio. He and his wife had no children, so his military acquaintances became like a second family to him. "Mild-mannered and soft-spoken, he had the reddish hair and florid complexion of an Irishman and also 'a temper when tested too far.' No drinker, something of a loner, he seldom mingled socially with his officers, but they had deep respect for his ability as a commander. The

greatest tests of Robertson's career involved the order he received to

attack the Roer River dams in early December, 1944, and the subsequent

crisis when that campaign was suddenly halted by the beginning of the

Battle of the Bulge (major German counteroffensive) in mid December (MacDonald, pp. 89-91). Robertson

skillfully led his forces during a remarkable defense and realignment on the Elsenborn

Ridge in the Ardennes.

At this time, Robertson's forces suffered tremendous hardships and

casualties when they successfully held the critical "northern shoulder" and

played a key role by slowing the Nazis advance, effectively preventing them from accomplishing

their goal of pushing to the Meuse River and ultimately taking Antwerp, as

the later account below shows. |

|

|

Darold Henson was a member of the 38th Regiment, which played a key role in the 2nd Infantry's successful campaigns throughout the European Theater, including the critical defense of the northern shoulder at the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge, as described later on this page. The commander of the 38th Regiment was Colonel Francis H. Boos, who was born August 13, 1905, in Janesville, Wisconsin. Boos had studied law for one year before enrolling at West Point, where he graduated in 1928. He was stationed throughout the U.S. as he rose through the ranks, joining the 2nd Inf. Div. as an executive officer of the 38th Reg. in the fall of 1942. When the 2nd Inf. Div. was

nearing the critical battle for St.-Lo in the Normandy campaign, Col. Boos

was wounded in the arm with shell shrapnel. Another officer next to him was

killed. "Since the 3rd Battalion then had no commander, Col. Boos, in spite

of the shrapnel in his arm, took over the battalion until Lt. Col. Barsanti was able to come from the 1st Battalion

and relieve him." |

Colonel

Francis H. Boos, (38th Regimental Combat Team, p. 3)

|

|

Col. Boos's greatest challenge and accomplishment came at the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge. Then, he skillfully guided the 38th Regiment's shift from offensive action in the attack on the Roer River dams on the eastern front to its critical defensive role in holding the "northern shoulder" when the German counteroffensive began on December 16, 1944. "Col. Boos is probably one of the most decorated men in the 2nd Inf. Division, holding three bronze stars, a silver star, the Combat Infantry Badge, two Croix De Guerres, the Eminent Order of Suvorov, presented by the Stalingrad-Kiev armored Guards Corps, together with the Order of War for the Fatherland, 2nd class, the Czechoslovakian Military Cross, and the Purple Heart" (38th Regimental Combat Team, p. 3). Note: I am most grateful to Mr. Norman L. Weiss for providing information about Col. Boos, including his photo.

|

|

|

Route of the First Army Taking Darold Henson Throughout the European Theater

Figure 1: Overview of the European Theater During World War II (adapted from Stephen E. Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, p. 108-109) Note: I have enhanced the source maps with red graphics and text to clarify the routes taken by Darold's units. Figure 1 shows the inexorable, advancing wave of the Allies moving eastward. The solid black line at the right-side of the map, nearly vertical, shows the Allies impinging ominously on the German border by the middle of September, 1944.

|

|

|

Darold Henson's Role as a Replacement Soldier Darold entered WW II as a replacement soldier. That is, the unit he belonged to was positioned immediately behind the front lines as a resource to replace fallen soldiers as needed. In Citizen Soldiers, Stephen Ambrose devotes an entire chapter, "Replacements and Reinforcements," to the U.S. Army's system of replacing lost soldiers in order to keep Divisions continuously on the front. The British and German system withdrew weakened divisions for rest and replenishment of personnel. American divisions that were in contact with the enemy from Normandy until they reached the German border were well over 100 percent replacements by December (and four--the 1st, 3rd, 4th, and 29th--were over 200 percent)" (p. 273). [Note: Glynn Raby points out that the 200 percent rate applies to the end of the war, not to the time the Americans reached Germany.] Ambrose is highly critical of this system because it did not adequately train soldiers, sometimes moving soldiers into combat within a month of drafting them. This system also forced soldiers to enter combat among strangers. Combat veterans tended to shun replacements because they talked too loudly, bunched together, and drew attention to the enemy. "Replacements paid the cost. Often more than half became casualties within the first three days on the line. The odds were against a replacement's surviving enough to gain recognition and experience" (p. 277). As a draftee in early 1944, Darold did not experience the abbreviated basic training that draftees later that year received. By the time many replacement troops were facing combat for the first time--on the front in the winter of 1944-45--, Darold was a veteran of fighting in Normandy and Brittany. He had beaten the odds against surviving that long. Darold recalls that in the Battle of the Bulge many men had to fight who had been serving behind the front in such support positions as cooks. He said some grumbled, but most did their duty.

|

|

|

Weapon Assignment Darold said that trainees were told they could have their choice of weapon type. He opted for artillery, but throughout his WW II Army service, Darold was assigned to squads operating .30-caliber water-cooled machine guns. Basic training also gave Darold experience with rifles and mortars. Darold's

"Separation Qualification Record" specifies his job title as "heavy machine

gunner 605," and this document includes the job description: "loads, aims,

cleans, maintains, and fires heavy machine gun to provide automatic direct

or indirect fire in support of other tactical units breaking through enemy

defense [lines]. Estimates, ranges, and sets sights. Is responsible for

control and co-ordination of machine gun squads and tactical employment of

weapons." |

|

|

.30-caliber Water-Cooled Machine Gun M1917A1 photo

from

www.rt66.com/~korteng/SmallArms/30calhv.htm |

Machine Gun Squad US Army photo from |

|

The photo above at the left shows a coolant container in the foreground. The .30-caliber water-cooled machine gun was a medium-sized machine gun. There was a smaller.30-caliber air-cooled machine gun as well. Darold says that the larger water-cooled weapon was more accurate than the smaller .30 caliber. Darold explained that the .30-caliber machine gun he was familiar with did not have the coolant can attached as seen in the above left photo. Rather, coolant was poured in from a capped hole on the top of the barrel. In the crucial winter fighting of 1944-45 in the Ardennes, Darold said that his squad often used calvadose as a coolant for their machine gun. Calvadose is a French apple brandy, whose high alcohol content prevents it from freezing. This coolant was plentiful throughout the region. Even so, he said the barrel became extremely hot. A seven-man squad was assigned to a .30-cal. water-cooled machine gun: first and second gunners and five ammunition ("ammo") bearers. Darold said that ordinarily he was an ammo bearer, but there were occasions when he had to fire the gun. This weapon was mounted on either a tripod or a flat base. Typically this weapon was fired from the ground but was sometimes fired from a vehicle. According to Darold, the ideal position for this weapon was on a rise about 100 yards behind the riflemen to allow protective firing over their heads ("overfire"). The ammo boxes were set near the weapon, and then the ammo bearers moved into their foxholes (often two in one foxhole) some distance behind the gun to minimize casualties. The gunner sighted the weapon by using knobs to coordinate the horizontal and vertical orientation. The combat that Darold experienced in Belgium and on the Schnee Eiffel in Germany allowed overfire positioning. In the hedgerow country, machine gunners fought next to the riflemen because there was no cover behind them. In those situations, the .30-caliber water-cooled machine gun was mounted on a base rather than a tripod. In that kind of situation, the gunner gripped the weapon with both hands to swivel, raise, and lower it--simultaneously aiming and firing. Darold recalled that early in the fighting his squad was given tracer bullets so the gunner could see where the bullets hit, but that later in the war the tracers were discontinued because they also gave away the gun's position.

|

|

|

The Battle for Normandy and the Hedgerows (June 6--August 15, 1944) Several units of Gerow's V Corps landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Robertson's 2nd Infantry Division landed on Omaha Beach the next day. Evidence was everywhere of the nearly disastrous first landing. Then, "heavy seas and bad weather complicated landing for the 34,142 soldiers and 3,306 vehicles of the initial assault wave. Almost three-fourths of the assault vehicles and artillery were lost . . . . Soldiers struggled through heavy surf and then across 200 to 300 yards of open, mined beach, and then found themselves pinned down behind a seawall or. . . line of dunes, by unexpectedly heavy fire. Eventually, they also discovered that virtually every unit had landed in the wrong place. . . . Omaha turned out to be the most tenaciously defended of the invasion beaches, and the site of the bloodiest fighting. . . . The first day of the war had been a sobering one. In 15 hours of combat, V Corps had taken approximately 2,500 casualties" ("V Corps on D-Day, June 6, 1944"). Omaha Beach fighting is realistically portrayed in the movie Private Ryan. The names of all beachheads from west to east were Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword (Botting, The Second Front). When Robertson's 2nd Infantry landed on Omaha Beach near St. Laurent-sur-Mer (D-plus 1), they found themselves "in the teeth of vicious, accurate enemy shellfire, which blanketed the shoreline. . . ." The assembling areas were "packed with snipers. Before moving in, one regiment was forced to blast out a company of Germans. . . ." The next day "a fusillade of sniper bullets spattered into the division command post" (Lone Sentry). Note: the American Cemetery at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer has 9,386 graves of American soldiers who died on the Normandy beaches. All Americans landing in Normandy who tried to advance southward immediately faced the challenge of fighting a determined, entrenched foe who had the special advantage of a readily defensible landscape. "No terrain in the world was better suited for defensive action with the weapons of the fourth decade of the twentieth century than the Norman hedgerows, and only the lava and coral, caves, and tunnels of Iwo Jima and Okinawa were as favorable" (Citizen Soldiers, p. 35). Americans in Normandy were challenged by fifty miles of hedgerow country, with "an average of 500 small fields per square mile" (Liberation, p. 21). Hedgerow country was "a patchwork of thousands of small fields enclosed by almost impenetrable hedges. . .dense thickets of hawthorne, brambles, vines and trees ranging up to 15 feet in height, growing out of earthen mounds several feet thick and three or four feet high, with a drainage ditch on either side. The wall and hedges together were so formidable that each field took on the character of a small fort. Defenders dug in at the base of a hedgerow and hidden by vegetation were all but impervious to rifle and artillery fire. So dense was the vegetation that infantrymen poking around the hedgerows sometimes found themselves staring eye to eye at startled Germans. A single machine gun concealed in a hedgerow could mow down attacking troops as they attempted to advance from one hedge to another. Snipers, mounted on wooden platforms in the treetops and using flashless gunpowder to avoid giving away their positions, were a constant threat. Most of the roads were wagon trails, worn into sunken lanes by centuries of use and turned into cavern-like mazes by overarching hedges" (Liberation, p. 17). The narrow, sunken roads were nearly useless to tanks.

Figure 2 below shows the approximate direction of V Corps toward St.-Lo, one

of the first major acquisitions in the quest to liberate France. Figure 3

below shows the irregular patchwork landscape of hedgerow country. |

|

|

Figure 2: V Corps in Normandy (adapted from Citizen Soldiers, p. 28)

|

(from Doubler, "Busting the Bocage") |

|

One of

the distinct advantages of American forces was its mobility, which depended

on artillery, the Sherman tank, and other armored vehicles as well as trucks

and jeeps. Hedgerows, however, prevented easy maneuverability. |

|

|

What was supposed to take days according to the Allies' plans actually took weeks of tedious fighting with heavy casualties and much equipment destroyed. The Sherman tank was a principal weapon of attack, but the hedgerows were barricades that tanks could not fire over or through. Figure 4 illustrates typical traits of hedgerows that made them ideal defensive barriers. "A major shortcoming of the Sherman [tank] for hedgerow fighting was its unarmored underbelly, which made it particularly vulnerable to the panzerfauust [crude, disposable but effective German mortar piece] when it tried to climb a hedgerow" (Citizen Soldiers, p. 66). Through "Yankee ingenuity," a couple of GI's began to experiment with welding large steel prongs to the front bumpers of tanks. Those devices enabled tanks to plow into hedgerows and fire into the next hedgerow and to break through the hedgerow so that other tanks and infantrymen could advance. The

photo below at the left shows the Culin cutter, named after its inventor

Sgt. Curtis Culin, who had been a taxi cab driver in Chicago. |

Figure 4: Hedgerow Cross Section (adapted from Lonesentry.com/normandy_lessons) |

|

Culin

Cutter: the Key to (from Liberation, p. 21) |

"Searching Hedgerow for Snipers: Soldiers Advance Past a Dead Comrade" (from Liberation, p. 21) |

|

In the slow advance toward St.-Lo, the 2nd Infantry fought for and took Tevieres, Le Molay, Foret de Cerisy, Berigny-St. Georges d'Elle, and St. Germain d'Elle before the decisive battle for Hill 192 from June 11 to June 16: "Thickly covered with heavy foliage, the hill commanded a six-mile area. . . . The enemy had been fortifying Hill 192 for months. It was studded with foxholes, machine gun nests, and expertly camouflaged observation points. Hedgerows sprouted along its gradual slope. Behind these, Germans huddled in dugouts. Every crossing and road in the vicinity had been zeroed in by enemy artillery emplaced on the rear slope. German camouflage suits blended softly with the foliage so well that one Nazi sniper remained in a tree only 150 yards from American lines an entire day before he was located and killed. When the 'Second to None' wrested the precious territory from the Nazis, the breakthrough at St.-Lo (vital communications center just six miles away) was set to following two weeks later" (Lone Sentry, p. 4). Various

American forces fought for and captured St.-Lo between July 17th and the

24th. Darold told me that when he was there, St.-Lo was in rubble.

Besides the ground fighting there, "St.-Lo had been hit by B-17's on D-Day,

and every clear day thereafter" (Citizen Soldiers, p. 75). |

|

|

St.-Lo was a key benchmark in the liberation of France and defeat of the Germans. Beyond St.-Lo, "the rout was on. . . . At times the Americans fell exhausted against the hedgerows, only to rise and slog wearily forward again. But what they paid in sweat, they saved in blood. The enemy had no time in which to dig in deeply and catch his breath for another stand" (Lone Sentry). By August 2, V Corps of the 2nd Infantry had crossed the Vire River, then took Vire, and proceeded southeast to take Tinchebray on Aug. 15 (see Figure 5). "The next day, the 2nd Inf. Div. drew out of action and for the fist time in the battle of the hedgerows, the 2nd no longer had the enemy to its front. It had come some 40 kilometers in 20 days. The breathing spell came none too soon." "In World War I, the 2nd Inf. Div. had set a record of 56 consecutive days of fighting. That mark was now eclipsed. World War II saw the Indian Head combat soldiers in the front lines 70 straight days--from D-Day plus 1 to D plus 71!" Of the

part the 2nd Inf. Div. played in the Battle of Normandy, Maj. Gen. L.T.

Gerow, Commanding General, V Corps, said: "The record of the 2nd Inf.

Div. from its arrival on the beaches of Normandy until the capture of Tinchebray

has been one of hard, relentless fighting against a stubborn enemy" (Lone

Sentry). |

Figure 5:

Route of V Corps (adapted from www.army.mil/) |

|

"It was largely through the persistent determination and unfailing courage of the officers and the men of the 2nd Inf. Div. that the battle of the hedgerows was won. For more than two months of continuous fighting, they were to a great measure responsible for the success of V Corps" (Lone Sentry). When Darold arrived in Normandy, he spent several days in a "replacement pool" (holding area) before he was trucked to St.-Lo. From there, he walked to the front. He first participated in combat toward the end of July or beginning of August, 1944, as the First Army advanced from St.-Lo toward Vire and Tinchebray. In December of 2004, Darold told me that one day when he was in the hedgerow fighting beyond St.-Lo, the soldier standing next to him fell dead from a sniper's bullet. In December of 2005, Darold said that one day as his seven-man machine gun squad was walking in file along a hedgerow, a German soldier suddenly jumped out of the brush and began firing with a burp-gun pistol. Darold, who was #6 in the squad, felt the heat of a bullet pass on the right side of his neck. He dove into the nearby wheat field and stayed there until dark, when he made his way back to his company. There he found squad member #2-- the only other member of the squad who survived the ambush. In the early August hedgerow fighting, Darold was wounded with shrapnel in the right leg near the knee. The wound was not serious enough to keep him out of action for very long. The

battle of the hedgerows (June 6--Aug. 15, 1944) exacted a heavy price on V

Corps, which suffered 2,500 casualties the first day of the war. The battle

of the hedgerows took another 3,300 casualties from V Corps for a total of

5,800 (V Corps on D-Day). "Almost

immediately after the fall of Tinchebray, the 2nd Inf. Div. of V Corps

embarked on a 300-mile journey and the Battle of Brest" (Lone Sentry).

Although the battle of the hedgerows in Normandy was over, Americans

continued to encounter hedgerows in other areas of France, including

Brittany near Brest. |

|

|

The Battle for Brittany and Brest (August--September, 1944) The 2nd Infantry Division

participated in the liberation of Brittany. The main target was the major seaport of Brest,

located

on the far western coast of Brittany. Early in the war, Brest had been bombed by the Allies

because the Nazis were using it as a submarine base, and the Nazis had

approximately 40,000 personnel in the immediate area. The Allies coveted all ports

in northern Europe for their potential value as entry points to supply

Allied forces. I find

no source that specifically traces the 2nd Infantry Division's exact route

through Brittany toward Brest. The

first American units in this campaign moved through Brittany in the first week of

August. The red arrows in Figure 6 below trace those routes approximately.

Most likely, the units including the 2nd Inf. Div. would have followed those

routes when they traveled through Brittany toward Brest after the middle of

August. |

|

Figure 6: Movement of First Army Through Brittany Toward Brest, August, 1944 (adapted from Sixth Armored Div. Association maps and Multimap.com) Darold saw combat in the fighting on the outskirts of Brest. The beginning of the 2nd Infantry Division's action in the Battle of Brest came on August 22, 1942--my second birthday. The Americans first assaulted German fortifications on the hills surrounding the city. These fortifications included pillboxes, tunnels, and foxholes. The 2nd Inf. captured the highest point overlooking the city (Hill 154), and this position then "produced an immediate advantage. TD [tank destroyers] artillery and heavy machine guns now could be set up along the shore, pouring direct, harassing fire across the harbor into the city" (Lone Sentry). Other, more heavily fortified hills were also captured in preparation for taking the city. Although heavy damage had been done inside the city, the Germans were entrenched there: "Traditional methods of street fighting were useless. These streets were death traps swept by machine and flak guns set up at intersections. Positions were gained by the 'ladder route,' through back doors, gardens, up and down ladders, and over walls and hastily improvised catwalks. Another expedient was to chop a path through the middle of the block by blasting interior walls. . . . Surrounding, flanking, working their way from block to block, sometimes knocking out a machine gun from an upper story window, or engaging in grenade and fire fights within building, the infantry inched forward" (Lone Sentry). On September 18, 1944, the day after Darold's 26th birthday, the Germans surrendered Brest. By September 21, German resistance in the Brest area had ceased. "In the course of fighting for the area, the Third and Ninth Armies took more than 37,000 prisoners [13,000 had been captured by the 2nd Infantry--Lone Sentry] and killed an estimated 4,000 Germans. The Ninth Army suffered approximately 3,000 casualties. . . . The port of Brest was too badly wrecked to be of an immediate value" (Pogue, "The Battles of Attrition, September--December, 1944"). After the fall of Brest, the 2nd Infantry Division was transported to the eastern front. [Note from Glynn Raby about the status of the 2nd Infantry Division after the fall of Brest: The 2nd Infantry Division "was still assigned to VIII Corps, 9th Army. VIII Corps was transferred to 1st Army October 22, and 2nd Division to V Corps when we left the Schnee Eiffel December 10-12." Glynn cites the 2nd Infantry Division History, pp. 80 and 83, as the source.] Note: My European correspondent, Mr. Ronan Urvoaz, has created a wonderful Web page tribute to the 2nd Infantry Division's noble work at the Battle of Brest. Please access his site by using the link below under Works Cited.

|

|

Occupation of the Schnee Eiffel and the Battle for the Roer River Dams (Oct. 4--Dec. 12, 1944) The dark arrows in Figure 7 below trace the routes of the Allies' advance in the fall and early winter of 1944 leading up to the critical Battle of the Bulge. The red circle on the map below shows the area where Darold Henson was positioned from early October, 1944, into mid December, when the 2nd Infantry was ordered to take the Roer River dams. That offensive action ended on December 16, 1944, when the Germans unleashed their all-out counteroffensive, which resulted in the Battle of the Bulge (December--January, 1945). As discussed later on this page, the goal of that German breakout attack was to take the seaport city of Antwerp and divide the Allies' forces, cutting off their supply route and provoking dissension among the Allied military and political leaders. On the way to the

eastern front, Darold's 2nd Inf. units traveled by railroad cattle cars

through Paris. Darold recalled seeing coal-fired train locomotives and French

farmers wearing wooden shoes. He said he first saw unisex restrooms when he

visited those facilities at the Paris train station. Darold said that a

significant number of soldiers left the cattle cars to visit Paris and

failed to return (wine, women, song, and sanctuary). |

|

|

Figure 7: Location of the 2nd Infantry Near Aachen (red circle) at Start of the Bulge (adapted from Stephen E. Ambrose, The Victors, pp. 218-219) In these advances, the 2nd Infantry Division traveled from Paris to St. Vith (north of Bastogne), then to the Hurtgen Forest and the Schnee Eiffel (mountain ridge between Bastogne and Aachen). Next, on December 7th, the 2nd Infantry was ordered to take the Roer River dams southeast of Aachen (see red circle in Figure 7). The campaign to take these bridges was halted when the German counteroffensive began on December 16. |

|

|

Figure 8 below shows the locations of St. Vith in Belgium, the Schnee Eiffel ridge, and the Roer River dams. The heavy black lines show the main thrusts of the mid-December German counteroffensive in this area. Note that one of these advances was at the location of the dams, threatening the 2nd Infantry. Also, note that Bastogne is located in the southwest region of Figure 8. The Roer River was an obstacle to the Allies' advance in that region. The Germans controlled the dams, and "the Americans would be foolish to put a single soldier across the river [downstream] unless they had the dams" (Miller, "Desperate Hours at Kesternich"). Americans downstream from the dams would be endangered by flooding if the Germans controlled or destroyed the dams. The significance of the dams, however, had not been taken into consideration in early strategic planning and had thus not been bombed by Allied air strikes, so that the V Corps would have to take the dams by ground attack. "The 78th Division would attack the Schwammenauel Dam, while the 2nd Infantry Division attacked the Urft Dam" (Miller).

No senior officer in V Corps had any illusion that the battle

would be easy; however, most of the officers were surprised at now difficult

the task turned out to be" (Miller). The "bone-chilling cold and fog"

complicated the offensive. Before the 78th could attack the Schwammenauel

Dam, it had to take the nearby town of Kesternich, which became the site of

bitter combat from December 13th through the end of the month. By the time

the 78th took the Schwammenauel Dam on February 9, 1945, the 78th Division had suffered

1,000 casualties. "The bitter fighting at Kesternich has been overshadowed

by the Bulge. . ." (Miller). As shown in "The Northern Shoulder of the

Battle of the Bulge" below, the 2nd Infantry faced its own arduous fighting

at this time. |

|

|

Figure 8: Roer River Dams (adapted from MacDonald, p. 31) |

Urft Dam on the Roer River (adapted from |

|

Darold was with units of the 2nd Infantry Division positioned on the Schnee Eiffel in October, 1944 (MacDonald, p. 104). Those units moved north when the 2nd Infantry prepared for its offensive to take the Roer River dams. Orders to begin that offensive were given on December 7 so the 2nd Inf. Div. left the Schnee Eiffel a few days later for that campaign. Darold said that action on the Schnee Eiffel was moderate: for example, mortar shelling to let the Americans know "the enemy was there." During one brief leave, Darold said he had a taste for some ice cream and was able to get a cone at a local village. Some of

the positions on the Schnee Eiffel formerly occupied by the departed 2nd

Infantry units were taken over by other U.S. forces. [Note: Glynn Raby

explains that "the 106th Infantry Division took over the Schnee Eiffel

positions from the 2nd Infantry Division December 10-12, and we moved

northward to the vicinity of Elsenborn. The 14th Cavalry filled the gap

between the 106th and 99th Divisions.] The 14th Cavalry was in the path of the

Germans when some of their forces advanced through the Loshiem Gap near

Loshiem (see Figure 8 above) on the northern end of the Schnee Eiffel at the beginning

of the Battle of the Bulge (December 16, 1944). |

|

|

Hitler's Counteroffensive Plan Leading to the Battle of the Bulge (Dec. 16--Jan., 1945) In the fall of 1944, the Allies had driven most of the German army back into its homeland, forcing the German military to fight defensively. Then, Hitler devised a surprise counterattack that he believed would divide the Allies and possibly produce circumstances that would enable him to win the war. In contemplating his limited options, Hitler ruled out any counterattack on the eastern (Russian) front because the distances were so great that supplying his army would be impossible and because the Russians greatly outnumbered the Germans. Hitler thus focused on his western front, where Germany bordered Belgium. He decided to attack toward the north in order to concentrate on the British and Canadian forces. He knew that the British did not have enough men to replace heavy casualties, and he believed that the Canadians would not want to replace heavy casualties. Given those speculations, Hitler believed the Americans would be unwilling to continue the war alone (MacDonald, p. 10). Hitler's strategy was to attack through the region known as the Ardennes and drive quickly to the Meuse River and then turn north to capture the seaport of Antwerp. Hitler knew that the survival of Nazi Germany demanded a successful counteroffensive. The Ardennes is a plateau region of northeastern France/southeastern Belgium encompassing approximately 400 square miles. The Ardennes extends west to the Meuse River in France, into Germany on the east, and into Luxembourg on the south. In Roman times the Ardennes was almost entirely forested. In the 1940s about half the region had been cleared, but dense forest remained. The population of the Ardennes was sparse and scattered in small villages of two- to five thousand inhabitants, but villages were important militarily because of their intersecting roads. In the fall of 1944, the war front in Europe stretched for hundreds of miles from the North Sea to Luxembourg. Because of the forbidding geography of the Ardennes, the Allies did not have heavy troop concentrations on the front in that region. "The Ardennes was at once the nursery and the old folks' home of the American command. New divisions came there for a battlefield shakedown, old ones to rest after heavy fighting and absorb replacements for their losses" (MacDonald, p. 83). Hitler well knew that the Ardennes was not strongly fortified by the Americans. The military leaders of the Allies had discussed the possibility of a German counterattack through the Ardennes but decided the probability was low (Eisenhower, pp. 100-101).

|

|

|

The Skepticism of Hitler's Generals That a Counteroffensive Could Reach Antwerp In the fall of 1944 when Hitler revealed his plan for a massive counteroffensive to his generals, they were either skeptical or incredulous that the German forces would ever reach Antwerp. Afred Jodl, chief of the Wehrmacht Operations Staff, proposed alternative invasion routes to that of the Ardennes, but Hitler rejected them (Eisenhower, The Bitter Woods, p. 28). When Commander-in-Chief Gerd von Rundstedt learned of Hitler's plan, Rundstedt called a meeting of other key commanders: Jodl, Generalfieldmarshall Walther Model, General der Panzertruppen Hasso von Manteuffel, General Joseph "Sepp" Dietrich, and General der Panzertruppen Erich Brandenberger. Mantueffel pointed out that reinforcements would be needed by the time the Germans reached the Meuse River, but that no such reinforcements were available (Eisenhower, p. 131). Manteuffel argued that a better plan would be for the German army, after pushing deep into the Ardennes, to turn north before reaching the Meuse River, thus "cut[ing] off all of the American First Army north of the penetration" (p. 132). Monteuffel, an avid bridge player, called his

alternative the "little slam" or "small solution." Rundstedt

argued that the attack through the Ardennes should be accompanied by a

simultaneous advance toward Antwerp from north of the Ardennes. Hitler and

his central planning staff dismissed these proposals. On December 2, 1944, in a

five-hour conference involving Hitler and 50 officers, Model and Manteuffel

again advocated the "small solution," but Hitler again rejected it

(Eisenhower, p. 142). |

|

|

Generalfieldmarshall Walther Model (from The Bitter Woods, unnumbered page) |

General der Panzertruppen Hasso von Manteuffel (from A Time for Trumpets, p. 251) |

|

The eminent WW II Historian Charles B. MacDonald analyzes the relationship between Hitler and his generals: "What the field commanders failed to recognize--or to accept--was the desperation that lay behind Hitler's plan, a desperation reinforced by the Fuhrer's megalomania and his distrust of his generals, whose ineptitude and disloyalty, he was convinced, were responsible for bringing Nazi Germany to the brink of destruction. . . . Destroying ten or fourteen to twenty American divisions around Aachen would not do it [the most that would come from "the small solution"]. He had to create conditions in which one nation could blame the other for the debacle that engulfed its troops, to sow mutual distrust, to deal such a blow that the people of Britain, Canada, and America would demand that their leaders bring their boys home" (A Time for Trumpets, p. 38).

|

|

|

Key Field Commanders in Hitler's Counteroffensive of December, 1944 In addition to reorganized and strengthened existing units, a key component of Hitler's strategy was the creation of "a new panzer army. It was to be commanded by. . . Joseph "Sepp" Dietrich, a longtime Nazi and early associate of Hitler's--a man utterly free of the stigma of the German General Staff Corps [which Hitler neither respected nor trusted] (Eisenhower, p. 113). Dietrich's Sixth Panzer Army and Manteuffel's Fifth Panzer Army were to lead the attack through the Ardennes simultaneously (Eisenhower, p. 116).

As soon as the first German units would break through the front lines, Otto Skorzeny's three task forces were to follow. One of these units featured

German soldiers who could speak English and who would be dressed as American

soldiers in order to foster confusion among the Americans. Another special

battle group (Kampfgruppe)--1st SS Panzer Regiment--, led by SS-Lt.

Jochem Peiper, was to accompany one of Skorzeny's units. Kampgruffen

Peiper's task was to drive as quickly as possible for the Meuse River,

bypassing opposition, not taking large numbers of prisoners, and

disregarding the need to protect his flanks (MacDonald, p. 89).

Clearly, Peiper's group was intended to be the key driving force in the

entire counteroffensive: "Kampgruppe Peiper was a powerful force of

approximately four thousand men. Peiper had seventy-two medium tanks, almost

equally divided between Mark IVs and Mark Vs (Panthers), roughly the

equivalent of one and a half American tank battalions. He also had five flak

tanks; a light flak battalion with self-propelled multiple 20mm. guns; about

twenty-five assault guns and self-propelled tank destroyers; an artillery

battalion with towed 105mm. howitzers; a battalion of SS-Panzergrenadiers;

around eighty half-tracks; a few reconnaissance troops; and two companies of

engineers [without bridge-building resources because this force was supposed

to move so rapidly]. Attached to Peiper were one of Skorzeny's four-man

teams disguised as Americans." Many other of Skorzeny's units were also

attached, including twelve Panthers [tanks] disguised to look like Shermans

[American tanks]. Other units of the 1st SS Panzer Division were to precede Peiper's forces and prepare the way for his rapid, overwhelming advance

(MacDonald, p. 198). |

|

|

Oberstruppenfuhrer Joseph "Seppe" Dietrich (A Time for Trumpets, p. 249) |

Obersturmbannfuhrer Lt. Col. Jochen Peiper (The Bitter Woods, unnumbered page) |

|

Unlike the standard German military cap--seen above in the photos of Model and von Manteuffel--, Dietrich's and Peiper's caps sported the skull and crossbones--no doubt a symbol of these men's determination to inflict death and destruction on the Allies. One of the technical reviewers of this page, former Lincolnite Dave Salyers, LCHS Class of 1959 and Army veteran, tells me that the scull and crossbones symbol on the villainous officers' caps is known as "'the Totenkopf'" (Death's Head) of the Waffen SS, which all W.S.S. members wore. (Waffen just means 'armed,' as in Luftwaffe.") (email message to me of 2-6-06). Peiper was infamous for his ruthlessness--on Germany's eastern front "he allegedly burned two

villages and killed all the inhabitants" (Eisenhower, p. 218).

As indicated later on this page, Peiper's soldiers murdered civilians and American

soldiers and were responsible for the most

heinous crime of the WW II European theater--the Malmedy Massacre.

According to Hitler's decree, the German counteroffensive in the Ardennes

should bring "a wave of terror and fright without humane inhibitions" (MacDonald, p. 197). German commanders implicitly and explicitly directed

their troops to take no prisoners and to spare no civilians who might be

visible in the streets, doors, and windows (MacDonald, p. 198). |

|

|

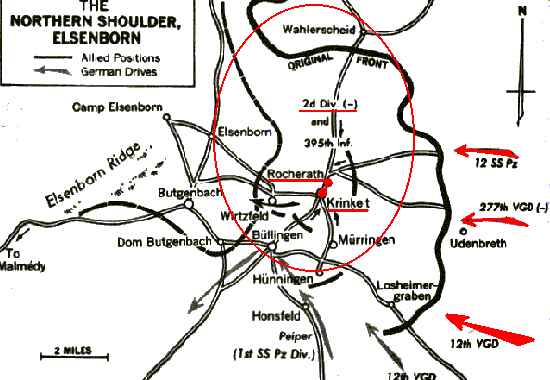

The Wahlerscheid Offensive and the Start of the Battle of the Bulge (Dec. 13--16)

Beginning in the second week of December, 1944,

several American units, including the 2nd Infantry Division, saw heavy

action in the area of Wahlerscheid and the "twin towns" of Rocherath and

Krinkelt. This area, shown in the red circle of Figure

9 below, lay just southeast of the Roer River Dams and

northwest of Malmedy, a town also identified on Figure 8 above. The 2nd

Infantry Division was positioned between Wahlerscheid (near the top of Figure 9) and the twin towns of Rocherath and

Krinkelt. This

heavy action was complex, reported here in summary, and a crucial part

of the Battle of the Bulge referred to as "the northern shoulder." When a military force advances and breaks through a

front line, the area immediately above and below the breakthrough is called

a shoulder. Conventional military strategy calls for effectively defending a

shoulder position ("holding a shoulder") to protect the flanks (sides) of

the defenders and thus to prevent defenders from being cut off and/or

surrounded. Holding the Northern Shoulder in the Battle of the Bulge (Dec. 13--21) The American positions indicated on the maps of this section were critical to containing and then halting the German counteroffensive. This heavy action only summarized here was complex and a crucial part of the Battle of the Bulge referred to as "the northern shoulder."

Figure 9: Position of the 2nd Infantry Division at the Beginning of the Bulge (12-16-1944) (adapted from John S.D. Eisenhower, The Bitter Woods, p. 222) |

|

|

Since approximately December 13th, two of Robertson's 2nd Infantry 38th regiment battalions had been trying to take the heavily fortified crossroad of Wahlerscheid (near top of Figure 9 above), and the third 38th battalion was "well forward in reserve" (MacDonald, pp. 180-181). [Note: the above map misspells Krinkelt. Also, Glynn Raby explains "our offensive started December 13, led by the 9th Infantry, with the 38th to come through the 9th and on to the dams after the crossroads was captured."] Wahlerscheid was a crossroads. This region was forested, and only one main road connected Wahlerscheid south to the twin towns of Rocherath and Krinkelt. The Germans had heavily fortified the area around Wahlerscheid with "mines, machine-gun nests, and barricades of barbed wire" (Hersko, Jr., "Winter Fury Near Elsenborn Ridge"). Robertson's forces had made slow progress, but Hersko reports that by December 16th, American forces had taken Wahlerscheid: "Evidence of the effort expended to capture Wahlerscheid was plain to see--shattered tree trunks stood starkly against the snow-covered ground, and branches littered the forest floor. Large, deep holes made by every type of shell were evident in great numbers. . . Then there were the men, tired and disheveled. Some walked around poking through the debris.

Others stood smoking cigarettes, silent. Still others laid out in neat,

straight rows, did nothing. The battle for Wahlerscheid was

over, but soon the Battle of the Bulge would unfold, and the survivors would

call it [battle for Wahlerscheid] "Heartbreak Crossroads" (Hersko).Somewhat different from Hersko's above description, historians John S.D.

Eisenhower and Charles A. MacDonald report that on December 17 Major General

Leonard T. Gerow, commander of V Corps, had decided it would be wise to

cancel the 2nd Infantry's attack that day at Wahlerscheid. Thus, Gerow

ordered V Corps to fall back to the Elsenborn Ridge and chose Robertson to

lead that movement (Eisenhower, p. 221). On December 17, Hodges gave Gerow

permission to take appropriate defensive action. Gerow thus decided to

withdraw the 99th and 2nd Divisions to the Elsenborn Ridge (Eisenhower, p.

221).

A significant development prompting Gerow's decision was the advance of

Jochen Peiper, leader of the 1st SS Panzer Division in the primary effort

first to reach the Meuse River and then take Antwerp--Hitler's master

counteroffensive plan to split the Allies forces. At the

beginning of the Bulge, Peiper first took Honsfeld, and then contrary to

Hitler's plan Peiper infringed on the route of other German forces by

turning north to Bullingen (see Figure 10 below), where he captured 50,000 gallons of gasoline

(Eisenhower, p. 220). Peiper decided to get back on track with his orders

and so headed west rather than turning north, where he would have overrun

the 2nd Infantry: "Americans from the 99th and 2nd divisions, their rear

areas exposed, were spared" (Eisenhower, p. 220). |

|

|

Figure 10: German Assault on Rocherath and Krinkelt December 17, 1944 (adapted from MacDonald, p. 373) |

Figure 11: Holding Elsenborn Ridge (adapted from MacDonald, p. 393) |

|

The decision to convert from offensive to defensive action in the Elsenborn region caused a crisis of leadership for the commander of the 2nd Inf. Div., in which Darold served: "General Robertson found himself faced with what was probably the most complex maneuver encountered by any division commander in World War II. In twenty miles of terrain Robertson had under his temporary command 18 intermingled infantry battalions. Some were under heavy attack; others were extended far to the north. His road net was strained by the presence of tanks, tank destroyers, artillery, and logistical units. Frontline units for the most part poked out into thick woods where fighting was difficult on both sides." "Robertson's two divisions were being hit by the might of the 12th SS Panzer Division and the 12th and 227th VG Divisions. Furthermore, he could look over his right shoulder and see that his main road to the rear was cut by Peiper's troops.

This is a situation that would have unnerved a lesser commander. Quiet, soft-spoken, and methodical, Robertson had commanded the 2nd Infantry Division without flourish but with unusual competence from the day of its landing in Normandy" (Eisenhower, pp. 221-222).

Robertson's plan was to withdraw in two phases: use the 99th Division [new to combat] and the 394th on the south to protect the two units that had been attacking at Wahlerscheid--the 9th Inf. and Darold's 38th Regiment, which had more recently begun to defend the twin towns of Rocherath and Krinkelt. "In one case a battalion of the 38th Infantry, placed in blocking position of the twin towns, was practically annihilated" (Eisenhower, p. 223). Once Robertson devised his plan and issued the orders, "he left his forward command post and moved up and down the road leading to Wahlerscheid [see Figures 9 and 11 above].

Through much of the rest of the day to come he would be driving up and down that road, watching the men of his division execute one of the most difficult of all military maneuvers: withdrawal in broad daylight in close contact with the enemy and in the face of violent enemy attacks from anther direction. The extinction or survival of the 2nd Division and much of the 99th Division hinged in large measure on Robertson's actions along that road" (MacDonald, p. 374).

The fighting in and around Rocherath and Krinkelt was brutal from December

17th through the 20th. During this time German forces tried to capture the

twin towns, and during this time "infantry and tank battles raged throughout

the villages. The streets and lanes of both were filled with wrecked and

burning tanks. Bodies of American and German dead were strewn about

everywhere, frozen into the grotesque positions that only violent death can

fashion. Men were captured, escaped and were recaptured. For hours GIs and

grenadiers fought one another separated only by a narrow road. Word that the

SS had been murdering prisoners and bayoneting wounded [at Malmedy] spread like wildfire

through the American ranks and as the battle for Krinkelt and Rocherath

continued--they neither gave nor expected quarter" (Hersko, "Winter Fury

Near Elsenborn Ridge").

(adapted from John S. D. Eisenhower, The Bitter Woods, p. 236) On December 19, despite the intense fighting, the various American units had maneuvered according to Robertson's plan, and the movement toward Elsenborn Ridge required the evacuation of the twin towns. "Colonel Boos ordered all equipment that could not be carried out of the villages to be destroyed. The Germans, still unwilling to give up, attacked throughout the day, but not on the scale of previous days. This was partially due to the fact that the 12th SS Panzer Division had been ordered to detour south and bypass the bottleneck, and continue on to the final objective--the banks of the Meuse River. . . . After three long, difficult days of practically nonstop combat (seven days for most of the 2nd Division), the initial phase of the battle around Elsenborn Ridge was over" ("Winter Fury Near Elsenborn Ridge"). Historians agree that the 2nd Infantry Division played a key role in wrecking Hitler's counteroffensive in the Ardennes. "Between December 13 and 19 the 2nd Division had penetrated a heavily fortified section of the West Wall, then executed an eight-mile withdrawal while in close contact with the enemy and assumed defensive positions at the twin villages facing in another direction. There they came immediately under heavy attack, held the villages for two days and nights while troops of the 99th Division streamed through, and then broke contact and withdrew to new positions on Elsenborn Ridge. . . . General Hodges told Robertson: 'What the 2nd Division has done. . .will live forever in the history of the United States Army'" (MacDonald, p. 409). "What the 2nd Division had done was to block an attack by Sepp Dietrich's Sixth Panzer Army constituting the main effort--the Schwerpunkt--of Hitler's offensive. . . . So, too, part of the credit for stopping the drive belonged to the inexperienced soldiers of the 99th Division" (MacDonald, p. 410). "The action of the 2nd and 99th divisions on the northern shoulder could well be considered the most decisive of the Ardennes campaign" (Eisenhower, p. 224). Although some units [of the 2nd Division] lost as much as 80 percent of their combat strength, the back of the German offensive in the Ardennes was effectively broken at the Twin Villages" (Hersko). "For the 2nd Division, [there were] just over a thousand men killed and missing, and since the division had few men captured most of those could be presumed dead" (MacDonald, p. 411). Americans fought other key battles at St. Vith and Bastogne. The fighting at Bastogne, of course, has garnered the most celebrated attention, but the other American victories need to be understood as well and the American sacrifices appreciated. The German counteroffensive in the Ardennes failed to advance the relatively short distance of twenty-six miles from its border with Belgium westward to the Meuse River. The German forces that advanced the farthest were Peiper's (see Figure 12 above). Besides the Americans' effective defense, Peiper was slowed by his difficulty in finding bridges substantial enough to support his tanks and by his rapidly dwindling fuel supply. "What Peiper did not know was that he was practically within spitting distance of enough gasoline to take him not only to the Meuse River but to the North Pole and back several times. In the woods along a secondary road only a few miles north of La Gleize was the second and larger of the First Army's big depots with more than 2 million gallons of gasoline [see Figure 12 above], guarded as night fell on the 18th by only about a hundred men of a rear echelon headquarters with five half-tracks and three assault guns reinforced by a few men of the Belgian Fusiliers" (MacDonald, p. 431). No efforts to reach and support Peiper were effective, including an airdrop. After several requests for permission to retreat, Peiper finally got it on December 22 with the stipulation that he take his vehicles and prisoners. Peiper knew he could not escape back to Germany if he could not walk unhindered by vehicles and prisoners, so he left them behind. By Christmas Day 1944, Peiper had reached Germany. In his failed campaign, dozens of tanks and other large vehicles had been lost or left behind. Also, "out of a force totaling 5,800 men, Peiper lost close to 5,000" (MacDonald, p. 463). Peiper's campaign was notorious for the crimes committed by some of his troops, especially the young SS fanatics. The most heinous example of murdering Americans occurred when Peiper's forces captured Malmedy (see Figure 12 above) on December 17, 1944. "Some of the 150 [American] prisoners were headed into a meadow by SS troopers and mowed down by machine gun and pistol fire. A few escaped by feigning death. Those who were detected as still alive were shot through the head with pistols. Approximately 80 men survived out of the 150 in the PW group. This was the infamous Malmedy Massacre" (Eisenhower, p. 237). SS troops also murdered Belgian civilians in "an orgy of killing in Stavelot, Trois Ponts, and the hamlets of Parfondruy, Ster, and Renardmont" (MacDonald, p. 438).

In the 1946 war trials at Dachau, Peiper was among the 43 Nazis sentenced to

death; Dietrich was among the 22 sentenced to life imprisonment (MacDonald,

p. 621). In 1949 Peiper's sentence was changed to life imprisonment

(MacDonald, p. 622). In 1954 his sentence was reduced to 35 years; however,

Peiper was released in 1956. He moved to the village of Traves, Alsace,

living with his family and working as a book translator. In 1976 an

inflammatory article appeared in the local press, and two weeks later

Peiper's home was firebombed, and he was killed (MacDonald, p. 623). Darold's Evacuation and Recuperation in the States Some time soon after the Battle of the Bulge began, Darold was evacuated because of trench foot--a problem of swollen, bleeding feet resulting from continuous exposure to water and freezing temperatures. Soldiers with serious cases of trench foot became disabled. Trench foot was a result of the wrong kind of footwear for harsh winter conditions. "The infantrymen's clothing was woefully, even criminally inadequate. . . . [An American general] had decided to keep weapons, ammunition, food, and replacements moving forward at the expense of winter clothing, betting that the campaign would be over before December. . . . [The American soldiers' footwear]--leather combat boots--was almost worse than useless. . . . Three days before the Bulge began, Col. Ken Reimers of the 90th Division noted that 'every day more men are falling out due to trench foot. Some men are so bad they can't wear shoes and are wearing overshoes over their socks. These men can't walk and are being carried from sheltered pillbox positions at night to firing positions in the day time'" (Stephen Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, p. 259). Stephen Ambrose describes the consequences of untreated trench foot: "First a man lost his toenails. His feet turned white, then purple, finally black. A serious case of trench foot made walking impossible. Many men lost their toes; some had to have their feet amputated. If gangrene set in, the doctors had to amputate the lower leg" (p. 260).

American Soldiers with .30-cal. Machine Gun in a Cold, Wet Foxhole in Belgium, Jan. 1945 (photo from Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, unnumbered page) Lt. Col. Walter R. Cook, the surgeon in charge of medical services for the 2nd Inf. Div., reported that in December of 1944, there were 153 cases of trench foot in comparison to 38 in November. "The hardships of winter warfare caused an increase in non-battle casualties, particularly in the incidence of combat exhaustion, trench foot, and frostbite. . . . The front line troops are literally living and sleeping in fox holes. This has prevented normal exercise of the lower extremities. By necessity the position underground has also been a factor in inhibiting proper circulation of the feet. . . . The ratio of battle casualties to non-battle casualties was approximately 1 to 1. The total non-battle casualties evacuated from the Division to the Clearing Station for December, 1944, was 1,971." Dr. Cook also describes the difficulties of evacuating casualties during the defense of the twin towns and withdrawal of the 2nd Inf. to the Elsenborn Ridge ("Headquarters Second Infantry Division Office of the Surgeon Medical Bulletin," Dec. 1944). Darold recalled spending Christmas Day, 1944, in a Paris hospital. From there he was flown to Britain on a C-47 and then transported to the U.S. on a hospital ship, departing on February 21, 1945, and arriving February 27. He recuperated in VA hospitals in Clinton, Iowa, and Indianapolis, Indiana, before being sent to Ft. Sam Houston for reassignment. I recall he once described hitchhiking home to Lincoln when he had a leave from the hospital in Clinton, Iowa. Later he was sent to Camp McCoy at Tomah, Wisconsin. There, because he was a veteran, he could live off the base. All that was required was that he report for daily morning roll call. Some of my first memories date to 1945 when Darold's mother (my Grandmother Ruth Henson) and I rode the train to see Dad in Wisconsin. On the train I enjoyed filling paper cups from the water cooler and running in the aisles. I also recall the commissary at Camp McCoy. The only other memory I have of Darold during his military service was his return to his mother's home late one night in 1945. I recall that a cab stopped in front of her house, and we went outside to greet Dad as he got out. I was surprised to see that the cab driver had a cast on his foot. Darold was honorably discharged from the Army of the United States at Camp McCoy on December 5, 1945. At the time of his discharge, he was paid $100.00 and $12.65 for travel expenses.

|

|

|

The Homecoming and the Memorabilia

Below:

Pfc. Darold Henson with his wife, Jane, and son. |

|

|

|

|

|

Family Portrait Hanging in

Ruth Henson's Living Room at 548 Fifth St., Lincoln, IL, from 1944-1986 |

|

|

"Overseas Cap" |

Dress Cap Tag |

|

Note: Glynn Raby provides the correct name for this kind of cap. He notes that "the red piping indicates Field Artillery." Leigh's note: Darold told me that he first attempted to be assigned to the artillery, but was transferred to the infantry. |

|

|

Army Uniform Dress Coat |

|

|

Button from Dress Coat |

|

|

Note: Glynn Raby explains that "insignia over the right pocket flap is an

Honorable Discharge badge. GIs called it a "Ruptured Duck." |

|

|

Darold's WW II Memorabilia Assembled by His Wife, Judy Henson Glynn Raby clarifies that the "large 'A' shoulder patch is the insignia for 1st Army. Darold is also eligible for the coveted Bronze Star, which he has never applied for. (See description of the Bronze Star at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bronze_Star_Medal.)

After the war Darold resumed his job

as bus driver and janitor at Lincoln Community High School (LCHS). For many

years, Darold was also the official timer for LCHS varsity basketball games. When he

retired from LCHS in 1977, he was the supervisor of buildings, grounds, and

transportation. LCHS Bus Drivers (l to r) Sam Zimmerman, Darold Henson, and Elmer Mosier (This photo from the 1949 Lincolnite, p. 80, was taken in front of LCHS on Broadway Street.)

|

|

|

Messages from Readers |

|

From Mr. Ronan Urvoaz, 5-5-06 Dear Mr. Henson, Let me congratulate you for your excellent work on your web site. I was born in Brest (Brittany, France) where your father experienced fear and hardship to secure our freedom. I have lived abroad for 15 years but I am still involved in honoring the memory of U.S. servicemen each year during the commemoration of the liberation of my home town. I have been researching the Battle of Brest for many years, I met many veterans on both sides, and with the help of historians we make sure that the sacrifice of those who didn’t come home is remembered for future generations. I came across this picture (see Massillon.jpg attachment) which was originally believed to have been taken during the siege of Cherbourg. I recently found the real location and identified the MG crew. They are members of H Co. 38th Infantry Battalion and this was probably taken on 10 or 11 September 1944 during the street fighting in Brest (see Massillon_ThenNow.jpg attachment). What is more remarkable is that the gunner could be your father, they really do look alike. It’s a long shot but I would appreciate if you took the time to share your views with me. Best regards, Ronan

Urvoaz Leigh's Response to Ronan Urvoaz Hi, Ronan, Judy Henson |

|

From Mr. Rick Crow, 7-22-06 Sir, This is one of the best accounts that I have come across since trying to find out more about my father's role in WWII. He was Lt. Ulrich W. Crow, 3rd Platoon, E Company, 2nd Infantry Division. Much like most veterans he did not tell much of his encounters. He joined the 2nd in August of 1944 about the time of the Brest invasion and was wounded on the second day of the Bulge and eventually ended up in a replacement depot (repple depple) in England as the war in Europe ended. I have not read this in detail but will print and do so. Thank you for such a great accounting. Rick Crow (U.W.C. Jr.)

Leigh's Response to Rick Crow Dear Rick, |

|

From Mr. Glynn Raby, 7-33-06 Hello, Leigh. I, too, am a WWII veteran of the 2nd Infantry Division. A French friend, Ronan Urvoaz, native of Brittany, called my attention to your webpage tribute to your Dad. I want to congratulate you on the excellent job you did in preparing it. It is really exceptional. Darold and I have a lot in common. We were both replacements and joined the 2nd Division in Normandy. We were both in battalion heavy weapons companies. I was in Co. H, 9th Infantry. We were both in MG platoons. But, I am younger, born in November 1924. Entered the Army March 1943, and served over a year with the newly formed 106th Infantry Division . As a replacement, was sent to Europe in May 1944. In a replacement camp in southern England on D-Day. To Omaha Beach a few weeks later and joined the 2nd Division in July. Survived Brittany, Schnee Eifel, Bulge and managed to avoid frozen feet. Made it through Germany and into Czechoslovakia at the war's end. I was discharged in October 1945, just a month prior to my 21st birthday. You did extensive research on the 2nd Division's part in the war, as evidenced by the list of publications cited. I recommend three more books for your further enlightenment: COMBAT HISTORY OF THE SECOND INFANTRY DIVISION IN WORLD WAR II was printed in 1946 by Army & Navy Publishing Co., Baton Rouge, LA. (I believe this was written by the division historian) Out of print, but re-printed by BATTERY PRESS, Nashville, TN. COMPANY COMMANDER by Charles B. MacDonald. (1947) (MacDonald's account of his experiences as a company commander in the 23rd Infantry) ISBN 1-58080-038-6 1944 AMERICANS IN BRITTANY, The Battle for Brest, by Jonathon Gawne. (2002) (a comprehensive description of the Brittany campaign, covering the breakout from Normandy and the actions of several armored and infantry divisions, and other units, culminating with the battle for Brest and the Crozon Peninsula) ISBN 2-913903-21-5

The author is the son of an 8th

Infantry Divison officer. The 8th was one of three divisions that

fought for BREST.

Glynn Raby Leigh's Response to Glynn Raby Dear Glynn, I am very grateful that you wrote to share a summary of your experiences, and I am most appreciative of the role you played in the keeping this country free. I can never thank folks like you enough for enabling my generation to have the opportunities it has enjoyed. Your compliment on my father's tribute page is much appreciated, and I am also most grateful for the corrections, additional details, and recommended sources. I will try to get a copy of the 2nd Infantry Division history for my dad. Within a few days I'll have the corrections and other info added to my dad's Web page, and certainly I will credit your for this substantial input. I am always glad to have a "technical review" of my writing on subject matter where I lack expertise. I will forward you message to my stepmother, and she will show it to Dad. He does not use a computer, but he will be very interested in your message. Sincerely, Leigh Henson |

|

From Mr. Richard

Schwab, 7-24-06

Mr. Henson,

I was just

informed about your excellent website honoring your father for his

actions in WW II. This meant a lot to me since I was a fellow

member of the 3rd Battalion of the 38th Infantry Regiment from June

1944 to September 1945. I was in Company I. Needless to say, I

never had the honor of meeting your father, but I know how much the

support of his company meant to us on every attack. We needed the

Heavy Weapons company constantly.

I am very

impressed with the extent and accuracy of your report. I have never

seen anything to equal it. You obviously spent many hours, yea,

many months, on this website. It is websites like this that will

finally get the message across to the rest of the world regarding

the enormity of the battle in the ETO.

I was with

Company I from June of 1944 until being discharged at Camp

Claiborne, Louisiana, in October of 1945. Just another "Citizen

Soldier" trying to get the job done as quickly as possible so we

could get home.

Glenn Raby, a

good friend of mine, told me about this website. If you got any

assistance from him you can "hang your hat on it." Glenn has a far

better mastery of the art of recall than I do.

Again,

congratulations. You have honored all of us in the "Second to

None"!!!

Dick Schwab

37572285

Company I

38th Regiment

2nd Infantry

Division

Leigh's Response

to Richard Schwab

Hi, Richard,

I'm glad Glenn Raby has directed you to my Dad's tribute page. I

appreciate learning of your service to this country, and thanks

for the compliment on my dad's page. I will forward your message

to him and add your message to the reader response section of

his page.

Warmest regards,

Leigh

From Mr. Ronan Urvoaz, 8-28-06

I

have been carrying on my research on the battle of Brest this

year and built a website in honor of 2nd Infantrymen like your

dad, I think you might want to have a look:

I

have just completed a detailed roster of the dead for the 9th

Infantry fallen during the battle of Brest and I am trying to

locate the families of each soldier to let them know that they

have not been forgotten and they will be remembered during the

next September commemorations of the liberation of Brest. Many

of them have already wrote me back, the response has been

outstanding from everyone in the States and everyone has been so

helpful. I am also working on a project to have a memorial built

dedicated to all units involved in the battle of Brest.

Leigh's Response Ronan, words can never express my gratitude for your wonderful tribute site. I will tell my father about it, and I know he will share my appreciation.

From Will Cavanagh, 8-29-06

Darold

While

surfing I came across your website telling of your father and his

role in WW2. Congratulations on a job well done !

Will Cavanagh

Author "Krinkelt-Rocherath the

Battle For the Twin Villages" and "The Battle East of

Elsenborn".

Leigh's Response: Mr. Cavanagh, I am deeply honored to receive your compliment. Note: Mr. Cavanagh is one of the world's leading authorities on WW II and the Battle of the Bulge. Please access the following site for more information: http://www.tours-international.com/Military+Tours/William+C+C+Cavanagh From Ronan Urvoaz,

9-29-06 |

|

From: Urvoaz, R. [UrvoazR@europol.eu.int] To: Henson, D. Leigh Subject: RE: Battle for Brest

Dear Leigh, The Ceremony began at 0930 Hrs with a moving speech from the Mayor of Brest paying tribute to the sacrifice of U.S. Troops. Flowers were placed on the Freedom Marker in Fort Montbarey’s courtyard. Taps was played and a minute of silence was respected. The Star-Spangled Banner and the Marseillaise were played to end the Ceremony. The following soldiers were honored: 1st Lt. John W. Case 224th FA, 29th Infantry Division S/Sgt. Armand P. De Clemente 28th IR. 8th Infantry Division Pvt. Thomas E. Doran, Jr. 38th IR, 2nd Infantry Division Pvt. Joseph T. Harris 9th IR, 2nd Infantry Division T/Sgt. Robert T. Lynn 28th IR, 8th Infantry Division Pfc. Richard C. MacDonald 28th IR, 8th Infantry Division Pvt. Francis J. Milne 9th IR, 2nd Infantry Division Pvt. Aral Moser 23rd IR, 2nd Infantry Division 2nd Lt John W. Schnepp 15th TB, 6th Armored Division Pvt. Eugene E Skahan 23rd IR, 2nd Infantry Division Pfc. Oscar Frederick Stephens 777th AAA, 6th Armored Division Sgt. Herbert L. Striker 5th Rangers Battalion Pvt. Lawrence C. Stockdale 23rd IR, 2nd Infantry Division Pvt. Albert Alfred Vincent 116th IR, 29th Infantry Division The cards are kept in the museum and placed on a wall, visitors coming to Fort Montbarey often marvels at the weapons, uniforms and vehicles on display without realizing how costly in human lives the Battle of Brest truly was. Hopefully, the many faces of these young men will serve as a permanent remainder for future generations. Best regards, Ronan |

|

Works Cited 38th Regimental Combat Team, Camp Carson, Colorado. Baton Rouge, LA: Army & Navy Publishing Company, 1947. Ambrose, Stephen. Citizen Soldiers: The U.S. Army from Normandy Beaches to the Bulge to the Surrender of Germany June 7, 1944--May 7, 1945. NY: Simon & Schuster, 1997. __________ . The Victors: Eisenhower and His Boys: The Men of World War II. NY: Touchstone, 1998. Battle of Brest Tribute Web site by Mr. Ronan Urvoaz: http://web.mac.com/ronan_urvoaz/iWeb/indianheads_brest/Home.html Blumenson, Martin. "Battle of the Hedgerows" in Liberation. Time-Life Books, Inc., 1978. Botting, Douglas. The Second Front. Time-Life Books, Inc., 1978. Cook, Lt. Col. Walter, M.D. "Medical Bulletin, Dec., 1944." Headquarters Second Infantry Division, Office of the Surgeon, APO #2, U.S. Army, January, 1945. http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/wwii/2dIDMedBullDec44.html. Doubler, Captain Michael D. "Busting the Bocage: American Combined Arms Operations in France 6 June--31 July, 1944." Combined Arms Research. http://www.cgsc.army.mil/carl/resources/csi/doubler/doubler.asp Eisenhower, John S.D. The Bitter Woods. NY: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1969. "German Dam Research and Technology": http://www.talsperrenkomitee.de/german_research/index.cgi)

Henson, Leigh.

About Lincoln,

Illinois;

This

Web Site; & Me. (an

account of Darold Henson's adult years) Hersko, Ralph E., Jr. "Winter Fury Near Elsenborn Ridge." Originally published in World War II Magazine, November, 1998. http://www.historynet.com/wwii/blelsenbornridge/index2.html WW II Illinois Veterans' Memorial Web site: http://ww2il.com. Access this site for information about purchasing commemorative stones for veterans of WW II. Information about weapons: http://www.rt66.com/~korteng/SmallArms/30calhv.htm. Also scroll to the .30 caliber. machine gun crew at http://www.warfoto.com/weapons.htm. Lone Sentry. From D+1 to 105: The Story of the 2nd Infantry Division. Originally published in Paris, France, by Stars & Stripes, 1944-45. Online version at http://www.lonesentry.com/gi_stories_booklets/2ndinfantry/ MacDonald, Charles H. A Time for Trumpets. NY: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1985. Note: in an email message to me Norman L. Weiss (12-7-05) explained that MacDonald "survived the battle at the twin cities as a young officer commanding a Company of either the 9th or 23rd Infantry Regiment. Most of his men were killed, and he fell back on the position held by Lt. Co. McKinley. He stayed with the Army as part of their historians." Glynn Raby explains that "Charles McDonald was company commander for Co. E, and later, Co. I, both 23rd Infantry." Miller, Edward G. "Desperate Hours at Kesternich." Originally published in World War II Magazine. http://historynet.com/wwii/blkesternich/index.html Parker, Danny S. Battle of the Bulge: Hitler's Ardennes Offensive, 1944-1945. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, Inc., 1991. V CORPS ON D-DAY, JUNE 6, 1944. http://www.vcorps.army.mil/ |

|

Email comments, corrections, questions, or suggestions.

Also please email me if this Web site helps you decide to visit Lincoln, Illinois: DLHenson@missouristate.edu. |

|

"The Past Is But the Prelude" |

|

|

|

|

|

|